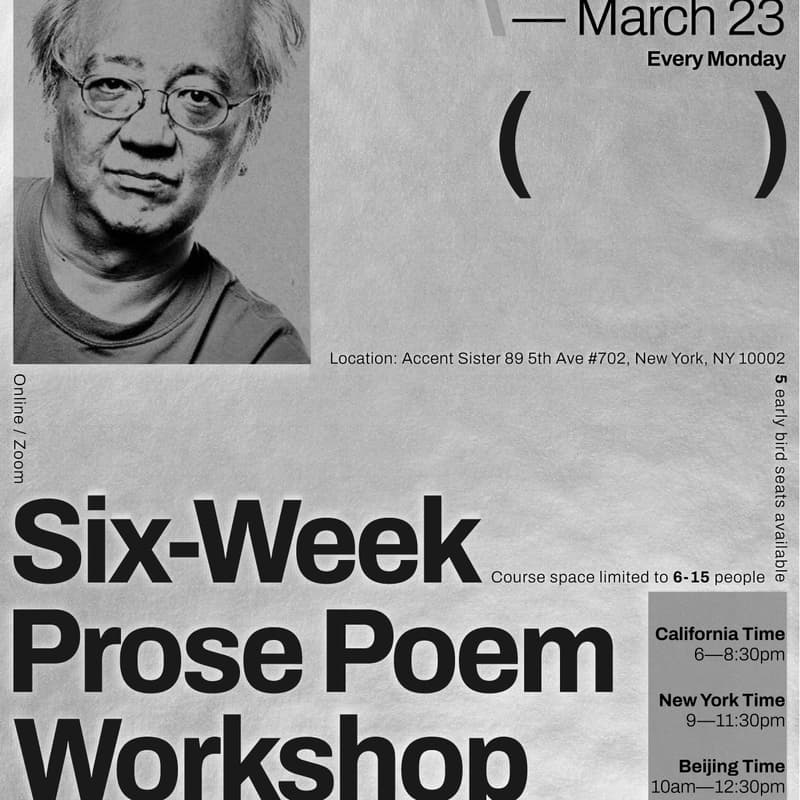

6 Weeks Prose Poem Workshop x John Yau

Accent Society has invited John Yau, veteran of the American poetry scene and art critic, to to be our mentor. I first encountered Yau as a freshman in college: at the time, I viewed poetry as a grave, autobiographical medium. However, reading and studying Yau’s poems taught me that it can be ludic and strange as well, and tapping into these traits was a significant step in unlocking the genre’s possibilities. As a teacher, Yau provides individual attention to each of his students and isn’t afraid to push them out of their comfort zone, in a process that leaves you transformed each time.

In his class “The Prose Poem,” students will explore the prose poem as a genre and learn how to pursue a sentence to its furthest possibilities. By the end of the course, students will have become familiar with different types of prose poems and written several of their own.

Course Overview

The form we will explore in the class is the prose poem. Charles Simic famously said, “The prose poem has the unusual distinction of being regarded with suspicion not only by the usual haters of poetry, but also by many poets themselves.” For one thing, prose poems are written in sentences. Sentences follow rules, as in the noun (as the subject) precedes the verb (action) precedes the object (The young girl sat on the sofa). What would happen if we substitute different sets of rules for the conventional ones we follow when writing sentences. Examples of what I am getting at can be found in writers who belong to a group known as OULIPO, which was founded in 1960 by Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais. The members of this

group developed mathematical and systematic constraints to generate new forms of writing. Georges Perec wrote a novel, translated as A Void, that did not use the letter “E” (this is known as a lipogram). There will be weekly assignments that the student will complete and send to me before class, so we can discuss them when the class meets. Each assignment will be constraint based. We will discuss other uses of constraints in poetry.

Workshop Time

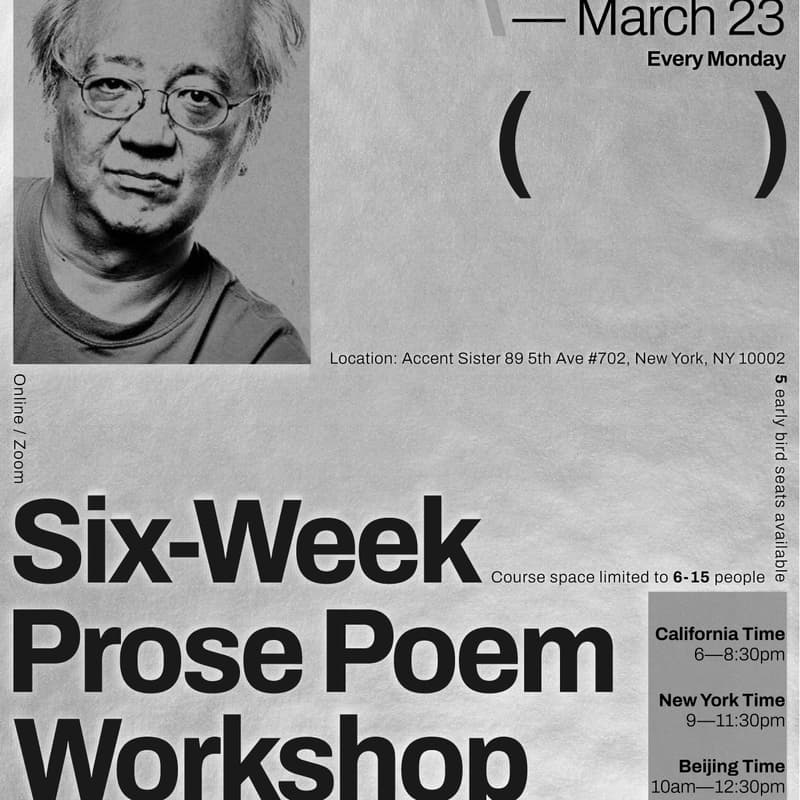

February 16 — March 23

Every Monday

California Time

6—8:30pm

New York Time

9—11:30pm

Beijing Time

10am—12:30pm

Course space limited to 6-15 people. 5 early bird seats available.

The workshop will once a week for six weeks, with each session running 2.5 hours in total. Students should read The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem: From Baudelaire to Anne Carson before the first class on February 16th, and be familiar with the poems of John Yau’s new poetry collection Diary of Small Discontents: New & Selected Poems 1974-2024.

Each class will be both a text discussion and revision session for students. Students will submit their poems to Professor Yau in advance so that they can be discussed during class time. By combining a historical study of the prose-poem with person experimentation in the form, students will deepen their understanding of the genre and leave equipped to continuing writing them beyond the course’s run-time.

Upon completion of the course, students will be able to trace the development of the prose poem from the mid 19th century to the modern day, as it has converged and diverged with other literary trends such as modernism and postmodernism. They will also learn how to write a prose poem with constraints and how to develop useful limitations in the future to challenge their writing abilities in daily practice. Moreover, each work will receive personal attention from the instructor, which will support the student in approaching and revising their own writing in the future.

This class is aimed at poets, prose writers, and experimental writers. If you enjoy playing with language, if you want to challenge yourself as you’ve never written before, if you’re in a writing slump and need to inject your craft with new life, if you want to create new avenues for telling old stories: this class is for you and will push you to become the most malleable writer that you can be.

Workshop Course Outline

Syllabus

Before the first class, the student read The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem: From Baudelaire to

Anne Carson sequentially, noting why they like some prose poems and not others, and why. We

will spend the first 15 minutes of each clas talking about prose poems, often zeroing in on one

from the anthology.

Assignments

Week 1:

Using the first vowel that appears in your name, the student should write a 7 to 12 sentence prose poem where every word you use has the first vowel in your name. for example, if your name is Edward, every word you use will have the letter “e” in it. There can be no exceptions. The student should write this for the class and be prepared to share it with the other students. We will try to read everyone’s work each time the class meets. There will be prompts given out at the end of class for the student work on during the week.

Week 2:

Write a pseudo-abecedarian. An abecedarian is a poem in which the first letter of each line or stanza follows sequentially through the alphabet. The prose poem will be 26 sentences long. The first sentence of your prose

poem will be with A, the second sentence with , until you have gone through the alphabet sequentially so that last sentence with begin with Z.

Week 3:

Pick a prose poem you like from the anthology. Choose a word from every sentence. Write a poem incorporating the words you have in the order you chose them. The word can be anywhere in the sentence.

Week 4:

The student makes a set of rules to be followed and uses it to write a prose poem.

Week 5:

The student makes another set of rules to be followed and uses it to write a prose poem.

About the Instructor

Poet, art critic, and curator John Yau has published over 50 books of poetry, fiction, and art criticism. Born in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1950 to Chinese emigrants, Yau attended Bard College and earned an MFA from Brooklyn College in 1978. His first book of poetry, Crossing Canal Street, was published in 1976. Since then, he has won acclaim for his poetry’s attentiveness to visual culture and linguistic surface. In poems that frequently pun, trope, and play with the English language, Yau offers complicated, sometimes competing versions of the legacy of his dual heritages—as Chinese, American, poet, and artist. A contributor for Contemporary Poets wrote: “Yau’s poems [are] often as much a product of his visual sense of the world, as his awareness of his double heritage from both Oriental and Occidental cultures.” Yau’s many collections of poetry include Corpse and Mirror (1983), selected by John Ashbery for the National Poetry Series, Edificio Sayonara (1992), Forbidden Entries (1996), Borrowed Love Poems (2002), Ing Grish (2005), Paradiso Diaspora (2006), Exhibits (2010), and Further Adventures in Monochrome (2012). Yau’s work frequently explores, and exploits, the boundaries between poetry and prose, and his collections of stories and prose poetry include Hawaiian Cowboys (1994), My Symptoms (1998), and Forbidden Entries (1996).

A noted art critic and curator, Yau has also published many works of art criticism and artists’ books. Reviewing Yau’s The United States of Jasper Johns (1996) a Publishers Weekly writer commented: “If you already have a weighty, profusely illustrated book on artist Jasper Johns but are still a little bemused, this is the book to buy.” Yau covers the career of the controversial neo-Dadaist painter, from his 1955 Flag to the 1993 After Holbein, deriving much of his text from interviews conducted with the reclusive Johns over a period of fifteen years. “In graceful, accessible prose,” the Publishers Weekly reviewer noted, “Yau deciphers the many art-historical sources within Johns’s art …[and] is capable of crafting the single phrase, such as ‘visual echo,’ that describes the activity within Johns’s work.” In addition to Johns, who he also wrote about in A Thing Among Things: The Art of Jasper Johns (2008), Yau has written on artists such as Andy Warhol, Joe Coleman, James Castle, and Kay Walkingstick. He has also collaborated with artists Archie Rand, Thomas Nozkowski, and Leiko Ikemura in poetry and art books like Hundred More Jokes from the Book of the Dead (2001), Ing Grish (2005), and Andalusia (2006). Calling Yau a “genius,” Robert Creeley described Ing Grish as a “brilliant train of wildly divergent thought.”

Yau has received many honors and awards for his work including a New York Foundation for the Arts Award, the Jerome Shestack Award, and the Lavan Award from the Academy of American Poets. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Ingram-Merrill Foundation, and the Guggenheim Foundation, and was named a Chevalier in the Order of Arts and Letters by France. Yau has taught at many institutions, including Pratt, the Maryland Institute College of Art and School of Visual Arts, Brown University, and the University of California-Berkeley. Since 2004 he has been the Arts editor of the Brooklyn Rail. He teaches at the Mason Gross School of the Arts and Rutgers University, and lives in New York City.

Reading Materials

The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem

From Baudelaire to Anne Carson

The last decades have seen an explosion of the prose poem. More and more writers are turning to this peculiarly rich and flexible form; it defines Claudia Rankine's Citizen, one of the most talked-about books of recent years, and many others, such as Sarah Howe's Loop of Jade and Vahni Capildeo's Measures of Expatriation, make extensive use of it. Yet this fertile mode which in its time has drawn the likes of Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, T. S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein and Seamus Heaney remains, for many contemporary readers, something of a mystery.

The history of the prose poem is a long and fascinating one. Here, Jeremy Noel-Tod reconstructs it for us by selecting the essential pieces of writing - by turns luminous, brooding, lamentatory and comic - which have defined and developed the form at each stage, from its beginnings in nineteenth-century France, through the twentieth-century traditions of Britain and America and beyond the English language, to the great wealth of material written internationally since 2000. Comprehensively told, it yields one of the most original and genre-changing anthologies to be published for some years, and offers readers the chance to discover a diverse range of new poets and new kinds of poem, while also meeting famous names in an unfamiliar guise.

Diary of Small Discontents

New & Selected Poems

John Yau

This collection brings together work from half a century of writing by John Yau. Preoccupied with forms and musical structures, Yau’s work includes sestinas, sonnets, pantoums, and lists, as well as invented forms. Employing both strict and open-ended frameworks, Yau creates multi-faceted poems that can shift abruptly from humor to outrage and consider topics including Chinese American identity, school shootings, invented countries, and haunted memories. Some poems are grounded in an autobiographical voice, while others take on the voices of other characters, including contemporary artists and a fictional Chinese private eye.

Further Adventures in Monochrome

John Yau

"Yau tweaks and twists language to express a painful comic vision in which sensual vividness combines with fierce despair."—Booklist

John Yau engages art criticism, social theory, and syntactical dexterity to confront the problems of aging, meaning, and identity. Insisting that "True poets and artists know where language ends, which is why they go there," Yau presses against the limits of language, creating poems that are at once cryptic, playful, and insightful. Included in its entirety is his groundbreaking serial poem, "Genghis Chan: Private Eye," and a new series invoking the monochromatic painter Yves Klein.

From "Exhibits":

Can you name which country uses selective amnesia to determine its foreign policy?

.

Money has become a vast dirty sea rolling over the land.

.

Money has become a UFO because it is the only thing that lacks controversy.

.

Money rhymes with algae.

.

Do you swear to tell the whole truth filled with nothing but reasonable lies?

.

Signing up for Free Membership works best in a failing economy.

.

In case of emergency, please vacuum the premises.

.

I used to be thorough, now I am just comprehensive . . .

Ing Grish

John Yau

Yau's comic and cutting poetry collides with the work of Nozkowski, whom the New Yorker has termed "the Chardin of contemporary abstraction." The end result is a dazzling and vibrant concoction of visual and written imagery. All the poems in Ing Grish are new, as are Nozkowski's paintings and illustrations, which he created expressly for this collection.

Ing Grish was named "Book of the Year" by Small Press Traffic in San Francisco.

Sample Prose Poems

A View of the Tropics Covered in Ash

John Yau

I began lying to myself at regular intervals, stopping by the side of the road only when it was necessary. The vegetation did not improve even as the interludes of pleasant shrubbery and herbaceous plants changed, and the waterfalls eventually became walls smothered in stains. I got tired of following myself back to the place where I was delivered; a howling newborn already indoctrinated that the mandibles of doom awaited me, along with other taunts and temptations too monstrous to mention. I did not have to sit long. We must all make dung, announced the boy with a smile full of crooked teeth. This was in the lobby where the first assignments were handed out. Where did you get those pearly gravestones screamed his toothless sister? What do you mean what do you mean moaned another vehicle headed for bedlam in an elastic waistband.

Life in an upscale suburb isn’t bad once you get used to hell. The suburban pageantry of soccer played with plastic skulls and rapacious bugs on a green summer day is worthy of an opera, complete with pouting male and curvaceous diva. Drugstores that deliver licensed drugs and pastel condiments are not to be sneezed at. There are plenty of tonics guaranteed to cure baldness, but impotency is something to be proud of, since it means your contributions to civilization’s convulsions are dwindling at an accelerated rate.

This is the time to begin concentrating on flying carpets, inexpensive episodes, and sitting in a rowboat on a speckled lake, dreaming of that moment long ago, when the first lie came to you unbidden. You are sleeping under a tree that reaches up past the bottom layer of starlit clouds. The lower branches are burning, just as you planned.

Unbidden

John Yau

I never have been a pallbearer. I did not help carry the coffins of my mother or my father—they died a few months apart—to their adjacent unmarked plots in a fenced-in cemetery on a suburban street near Burlington, Massachusetts, where they and my brother moved after I graduated from high school. Twice, I selected a coffin and paid for it with my credit card, but I never felt the actual physical weight of their death.

It was a bright and sunny morning when my father called. An hour later I was carrying a large cardboard box to the post office. That is when I saw her and did not know what to say when—for the first time—she stopped in front of me, smiled and said: how are you?

We are standing close together, in a zone not quite penetrated by what was around us. We had been smiling at each for weeks, maybe longer—whenever we passed each other, usually on a Saturday on West Broadway when everyone was going to art galleries—but we had never stopped to say hello to each other before because one of us was always with someone else. I stood there and said: I am well. I am going to the post office and looked at the unwieldy box I was carrying. I gave her a weak smile and shrug and I walked away and never saw her again.

I left that afternoon on a plane and made my way to my parents’ house, a place I stayed but where I never lived because I did not have a room there. I did not talk to anyone about what had happened. When she said hello and smiled, I was still hearing my father tell me that my mother had just died. He said that the last thing she said to him was how disappointed she was in me, and that I was clearly a failure of a son. A few moments later she had a heart attack and fell down the stairs. He had waited a long time to say these things to me in a calm, matter-of-fact voice, things my mother never said. I could hear him smiling loudly behind his report.

I stood there looking at a woman that I was smitten over and daydreamed about and all I could manage to do was mutter a few meaningless pleasantries.

I walked away.

I walked away wondering: is this what it means to be a poet?

You carry boxes to the post office.

You are tongue-tied and lost.

Whatever you want to say will not be said in this lifetime.

Documentary Cinema

John Yau

Money moves the heard, divides the nods from the hard-noses, keeps others lacquered shut. Occasionally, unexpected turbulence from a recalcitrant stump lantern introduces confusion, but these interruptions are not unexpected and easily papered over. While across the aisle, another globe sets off sparks. What animal do you most resemble when you are not an armadillo, surrounded by sordid ornaments, sweaty to the touch? Tender bellow mortified by fat. Postcard gargoyle in need of a second bath. Mouth full of severed thumbs. Pauses in leaky silence, station changes, climb into latest examples of a ruined civilization, what we call the present. Moon pasted frozen bright on wall near names of repeatedly missing. Adjacent ot commuter clatter, some filled with hard eyes. Wheel cover pandering to paper blocks, championing virtues of carbon trash, rods circulating cups on ice, another bleeding sky cools at its own pace.

Hysteria

T.S. Eliot

As she laughed I was aware of becoming involved in her laughter and being part of it, until her teeth were only accidental stars with a talent for squad-drill. I was drawn in by short gasps, inhaled at each momentary recovery, lost finally in the dark caverns of her throat, bruised by the ripple of unseen muscles. An elderly waiter with trembling hands was hurriedly spreading a pink and white checked cloth over the rusty green iron table, saying: ‘If the lady and gentleman wish to take their tea in the garden, if the lady and gentleman wish to take their tea in the garden …’ I decided that if the shaking of her breasts could be stopped, some of the fragments of the afternoon might be collected, and I concentrated my attention with careful subtlety to this end.

Meditations in an Emergency

Frank O’Hara

Am I to become profligate as if I were a blonde? Or religious as if I were French?

Each time my heart is broken it makes me feel more adventurous (and how the same names keep recurring on that interminable list!), but one of these days there’ll be nothing left with which to venture forth.

Why should I share you? Why don’t you get rid of someone else for a change?

I am the least difficult of men. All I want is boundless love.

Even trees understand me! Good heavens, I lie under them, too, don’t I? I’m just like a pile of leaves.

However, I have never clogged myself with the praises of pastoral life, nor with nostalgia for an innocent past of perverted acts in pastures. No. One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes—I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life. It is more important to affirm the least sincere; the clouds get enough attention as it is and even they continue to pass. Do they know what they’re missing? Uh huh.

My eyes are vague blue, like the sky, and change all the time; they are indiscriminate but fleeting, entirely specific and disloyal, so that no one trusts me. I am always looking away. Or again at something after it has given me up. It makes me restless and that makes me unhappy, but I cannot keep them still. If only I had grey, green, black, brown, yellow eyes; I would stay at home and do something. It’s not that I am curious. On the contrary, I am bored but it’s my duty to be attentive, I am needed by things as the sky must be above the earth. And lately, so great has their anxiety become, I can spare myself little sleep.

Now there is only one man I love to kiss when he is unshaven. Heterosexuality! you are inexorably approaching. (How discourage her?)

St. Serapion, I wrap myself in the robes of your whiteness which is like midnight in Dostoevsky. How am I to become a legend, my dear? I’ve tried love, but that hides you in the bosom of another and I am always springing forth from it like the lotus—the ecstasy of always bursting forth! (but one must not be distracted by it!) or like a hyacinth, “to keep the filth of life away,” yes, there, even in the heart, where the filth is pumped in and courses and slanders and pollutes and determines. I will my will, though I may become famous for a mysterious vacancy in that department, that greenhouse.

Destroy yourself, if you don’t know!

It is easy to be beautiful; it is difficult to appear so. I admire you, beloved, for the trap you’ve set. It's like a final chapter no one reads because the plot is over.

“Fanny Brown is run away—scampered off with a Cornet of Horse; I do love that little Minx, & hope She may be happy, tho’ She has vexed me by this Exploit a little too. —Poor silly Cecchina! or F:B: as we used to call her. —I wish She had a good Whipping and 10,000 pounds.” —Mrs. Thrale.

I’ve got to get out of here. I choose a piece of shawl and my dirtiest suntans. I’ll be back, I'll re-emerge, defeated, from the valley; you don’t want me to go where you go, so I go where you don’t want me to. It’s only afternoon, there’s a lot ahead. There won’t be any mail downstairs. Turning, I spit in the lock and the knob turns.

from Angle of Yaw

Ben Lerner

The first gaming system was the domesticated flame. Contemporary video games allow you to select the angle from which you view the action, inspiring a rash of high school massacres. Newer games, with their use of small strokes to simulate reflected light, are all but unintelligible to older players. We have abstracted airplanes from our simulators in the hope of manipulating flight as such. Game cheats, special codes that make your character invincible or rich, alter weather conditions or allow you to bypass a narrative stage, stand in relation to video games as prayer to reality. Children, if pushed, will attempt to inflict game cheats on the phenomenal world. Enter up, down, up, down, left, right, left, right, a, b, a, to tear open the sky. Left, left, b, b, to keep warm.

The Most Sensual Room

Masayo Koike

translated by Hiroaki Sato from the Japanese

One wall of the bathroom of Jay’s apartment has a cat’s footprints. Absence is something like that. To leave evidence. I see it. By rolling the world back. The way the cat ran up the wall and escaped out of the window. The wind that came in just as the cat left knocked down everything it touched by reversing time, from the small past in which the cat had disappeared, toward the present. The wind, having substantially disturbed the proper position of a light letter on the desk, has now passed by. And it is no longer here. Jay and I are contained in the room. And yet, the room feels vacant, somehow. Am I here? Clearly exist here? I am passing through it. I will become absent.

From the open window I hear the sounds of the neighbor’s house. Why aren’t you finishing your homework? The noise of plates. Would you come here and help me a bit? The noise of plates. What did you do with that? The noise of a washing machine. The soft ringing of a telephone. Hello, hello? Hello, hello? The beep signaling that the washing machine finished its work. We don’t know the faces of our neighbors. Nonetheless, they come in. Like a flood. Our neighbors’ daily routines, into this vacant room.

Jay and I turn on music. A brief conversation. Sexual intercourse. Laughter. The sound of slapping flesh. Two people cursing each other. These noises, too, slowly go out. Toward our neighbor’s house. Unobtrusively, directly. We languidly blend with one another, with voices alone. On the ground separating us ivy leaves overgrow.

The Sunday morning when I leave Jay’s room. There is Jay’s room where I no longer am. I don’t leave a single footprint, but my invisible fingerprints are imprinted everywhere. Nights, I think of the room. I peer out of the window. I see the absences of myself and the cat. Jay is a man who is part of that room. His long body tightly coiled into hardness, he, the penis of the room, is quietly asleep. I stretch my hand and touch the room. The wall is soft. I push the room harder, and the room goes out of the room. The room that contains nothing, except Jay, at first with some bounce, like a soap bubble, goes out of the hard room, slowly.